I picked a good week to make the bear's case for e-books. Amazon just announced a new Kindle. It's smaller and lighter than ever, and if you are willing to forego the 3G and just get books via wifi, the entry level price is now $139.

And BN is putting huge Nook boutiques in all of its stores.

On the other hand, the falling prices for hardware are indicative of the fact that 1.) the market for expensive e-readers is exhausted and 2.) the iPad is cutting into the market for these devices, and the price lever is the only weapon dedicated e-readers have against the all-purpose juggernaut.

or

3) Instead of subsidizing e-books to make money on hardware, Amazon is now subsidizing hardware to make money on e-books. Maybe the self-published and Amazon-published titles are looking very lucrative.

Friday, July 30, 2010

Wednesday, July 28, 2010

10 Reasons E-books Will Not Eat The World (part 2)

The exciting conclusion of yesterday's discussion:

5. Requiring hardware limits the audience. Despite apps that make e-book content available on PC or cell-phones, most e-books are sold to people who have e-readers. The subset of people who have e-readers is a small fraction of the total number of people. Even if this number grows exponentially in the next few years as devices get better and cheaper, it will still be far smaller than the total number of potential readers.

If e-sales begin taking a big bite out of print sales bookstores become an endangered species. There's no way publishers can achieve sales growth by focusing on the smaller audience of e-readers if bookstores are closing en-masse. I think that the relationship between publishers and bookstores is symbiotic, and publishers likely need many people who are becoming e-book buyers to patronize bookstores, to keep the stores solvent to provide a forum to sell to more causal readers who will probably never purchase dedicated reader devices.

There have already been discussions of delayed e-releases of frontlist titles, and publisher pushback on low e-book pricing. It's possible that e-books will become a genie nobody can stuff back into the bottle, but for now, the growth and spread of these devices is heavily contingent on support from major publishers. There have been fights between publishers and e-vendors in the past, and there are big new feuds on the horizon. Uninterrupted geometric sales growth of e-books seems unlikely if publishers push against it, and Amazon may not be as willing to go to the mattresses as the market becomes more segmented and its share of e-book sales shrinks.

4. Multipurpose devices aren't good for reading books. An LCD screen like the one on the iPad is back-lit. It displays an image by shining light through the screen. A lot of people don't like doing close reading on these kinds of screens for hours at a time. E-distribution of books has been possible for years, but there was never a market before e-readers came out because people didn't want to read books on their computers. Now many analysts believe e-books will conquer the market by piggybacking on devices like cell phones and iPads. But these devices use the same kinds of lit screens as laptops (and the screens on smartphones are very small).

These screens can also be difficult to view from certain angles, they're hard to read in sunlight, and they drain batteries pretty quickly. The experience of reading a book on an iPad is significantly worse than reading on paper. Even if these devices become ubiquitous, I think most users will continue to buy conventional books.

On the other hand, if you are reading this, you are probably reading on a backlit screen. And screens have replaced a lot of paper in many office uses; e-mail has displaced a lot of fax printouts and photocopies.

Some people think advancing technology will fix all these problems; Shatzkin predicts an iPad that folds or collapses into an iPhone. On a long enough timeline, anything is possible, but the magical device that is both LCD and e-ink, and both phone and pad is not coming anytime soon.

3. E-readers aren't good for anything but books, and are worse than books at being books. Dedicated reading devices like the Kindle use a screen technology called e-ink that "prints" the page onto a non-lit screen. These screens come close to simulating the appearance of paper; they look good in direct light and consume very little power.

The screen contrast isn't great; instead of black ink on white paper, you get dark-gray text on a light-gray background. But the screens are improving, and the delay when a page "turns" and the device draws in a new one is likely to shorten as well.

These devices bring some nice features; you can change the font size, and a text-to-speech robot voice can read books to you. But you can't flip back and forth as easily as you can with paper. And it's a technology device. If you drop it, you break it. If you sit on it or step on it, you break it. If you fall asleep in bed with it and roll on top of it, you break it. If it gets wet or if sand gets in its guts at the beach, it probably breaks. And if you leave it someplace you're out a lot of money. A book can survive most of these stresses, and if you lose or destroy it, you're out $16 bucks at the high end.

E-distribution of books has some obvious potential business efficiencies, but from an everyday-use perspective, an e-reader is a flawed solution to a problem that doesn't exist.

Obvious exceptions to this rule: literary agents and editors who have to schlep a lot of manuscripts around, and students who have to carry lots of textbooks. E-readers can make such cumbersome tasks much easier.

2. Author autographs. Go ask Cormac McCarthy to sign your iPad and see what happens.

Actually, that would be hilarious. If I ever meet him, I am going to do that.

5. Requiring hardware limits the audience. Despite apps that make e-book content available on PC or cell-phones, most e-books are sold to people who have e-readers. The subset of people who have e-readers is a small fraction of the total number of people. Even if this number grows exponentially in the next few years as devices get better and cheaper, it will still be far smaller than the total number of potential readers.

If e-sales begin taking a big bite out of print sales bookstores become an endangered species. There's no way publishers can achieve sales growth by focusing on the smaller audience of e-readers if bookstores are closing en-masse. I think that the relationship between publishers and bookstores is symbiotic, and publishers likely need many people who are becoming e-book buyers to patronize bookstores, to keep the stores solvent to provide a forum to sell to more causal readers who will probably never purchase dedicated reader devices.

|

| "I don't want to go to the mattresses. Tessio wets the bed." |

4. Multipurpose devices aren't good for reading books. An LCD screen like the one on the iPad is back-lit. It displays an image by shining light through the screen. A lot of people don't like doing close reading on these kinds of screens for hours at a time. E-distribution of books has been possible for years, but there was never a market before e-readers came out because people didn't want to read books on their computers. Now many analysts believe e-books will conquer the market by piggybacking on devices like cell phones and iPads. But these devices use the same kinds of lit screens as laptops (and the screens on smartphones are very small).

These screens can also be difficult to view from certain angles, they're hard to read in sunlight, and they drain batteries pretty quickly. The experience of reading a book on an iPad is significantly worse than reading on paper. Even if these devices become ubiquitous, I think most users will continue to buy conventional books.

| "Wait. What happened?" |

Some people think advancing technology will fix all these problems; Shatzkin predicts an iPad that folds or collapses into an iPhone. On a long enough timeline, anything is possible, but the magical device that is both LCD and e-ink, and both phone and pad is not coming anytime soon.

3. E-readers aren't good for anything but books, and are worse than books at being books. Dedicated reading devices like the Kindle use a screen technology called e-ink that "prints" the page onto a non-lit screen. These screens come close to simulating the appearance of paper; they look good in direct light and consume very little power.

The screen contrast isn't great; instead of black ink on white paper, you get dark-gray text on a light-gray background. But the screens are improving, and the delay when a page "turns" and the device draws in a new one is likely to shorten as well.

These devices bring some nice features; you can change the font size, and a text-to-speech robot voice can read books to you. But you can't flip back and forth as easily as you can with paper. And it's a technology device. If you drop it, you break it. If you sit on it or step on it, you break it. If you fall asleep in bed with it and roll on top of it, you break it. If it gets wet or if sand gets in its guts at the beach, it probably breaks. And if you leave it someplace you're out a lot of money. A book can survive most of these stresses, and if you lose or destroy it, you're out $16 bucks at the high end.

E-distribution of books has some obvious potential business efficiencies, but from an everyday-use perspective, an e-reader is a flawed solution to a problem that doesn't exist.

Obvious exceptions to this rule: literary agents and editors who have to schlep a lot of manuscripts around, and students who have to carry lots of textbooks. E-readers can make such cumbersome tasks much easier.

2. Author autographs. Go ask Cormac McCarthy to sign your iPad and see what happens.

Actually, that would be hilarious. If I ever meet him, I am going to do that.

1. Piracy. Because books are an analog format, they have a sort of built-in copy protection. You can't "rip" a book the way you can copy a music CD. To upload a book for file-sharing, somebody must either scan every page or transcribe the text into a computer file. Because of this structural difficulty, books have been largely spared the piracy troubles that music has struggled with over the last decade.

However, with e-books, if somebody manages to crack the encryption on one of these e-book file formats, then everyone's content will be available for free in clean, publisher-formated digital versions. And hacker-types have a history of accomplishing difficult things.

|

| "I've been listening to Ke$ha and reading 'Twilight' for free!" |

It seems likely somebody will eventually crack one of these formats. What will happen when that occurs? How will publishers and vendors react? We know Amazon can remove files from Kindles; they've done it before. Maybe vendors will wipe all the devices to prevent books from getting ripped. I think that would deal a serious blow to consumer confidence in e-books. On the other hand if they don't take an extreme response, widespread piracy could quickly devastate legitimate sales.

Tuesday, July 27, 2010

10 Reasons E-books Will Not Eat The World (part 1)

A lot of experts and analysts believe that the sales of e-readers and e-books will continue to grow exponentially, and that e-books will cannibalize the market for conventional books. It seems to be conventional wisdom that 50% of books will be in electronic formats within five years.

I don't have all the data that these people have, but I was an early-adopter of the Kindle (I have the first-gen model) and I've read a number of books on the device. For me, the novelty has worn off, and many people will likely come to this conclusion in the next year or two. If my experience is common, I think sales will plateau sooner than many analysts expect.

Here's why:

10. Conventional books can't really be improved on. A book is text on a page. You can't make a book better by making it a digital file; there's no way technology can alter or improve the experience of reading text on a page. A book cannot be remastered in high-definition. You can't make it faster. The best an e-book can possibly do is match the experience of reading a conventional book.

|

| "We need to reschedule your bar mitzvah. The Torah has a dead battery." |

9. Switching to e-books doesn't improve your life. Imagine it's 2002 and you're switching from music on CDs to an iPod. By adopting this format, you've gained access to a lot of new functionality and a lot of convenient features. You can now carry all your music with you, which is something people want to do. You no longer need to have a huge multidisc changer in the trunk of your car, or a multi-disk carousel in your home stereo. You no longer need to commit to listening to one artist or mixtape when you go for a run, and the physical device you will carry is much smaller than a CD player. You can construct playlists for various purposes, or you can shuffle all the songs on the device.

By contrast, consider how your life improves when you switch to the Kindle. You can carry a bunch of books, but do you really need to? Most people only read one book at a time. There's no playlist or shuffle-type features that you can utilize with your book library. The device is smaller than a hardcover, which is convenient if you're carrying it around in a handbag, but it's about the same size as a trade paperback.

Instant delivery of e-books is nice, but it's not compelling. I buy several books at a time, and I rarely run out of stuff to read, so I never need a new book immediately.

E-readers really offer no features that make the format or the device indispensable. There's no killer app here that makes an e-reader better than a book.

8. The price differential is disappearing. Theoretically, e-books should wipe out conventional books because of efficiency. A conventional book must be printed and bound and shipped and warehoused and often shelved and sold in a bookstore. Each of those things costs money. An e-book is an electronic file and distributing it is as trivial as sending an e-mail.

|

| "Once you get used to location codes, you won't miss page numbers." |

When Amazon first started selling e-books, it paid the same wholesale price for an e-book that it paid for a hardcover book, but it sold them at a loss, for $9.99. Hardcovers were selling for $17 a couple of years ago, so an e-book cost about half as much as a hardcover. Now, though, publishers have pushed back on Amazon's $9.99 pricing, and many e-books cost more. Meanwhile, hardcover pricing has been pushed down to about $15. So an $8 price difference has shrunk to around $2-3. And for titles published in trade or mass-market paperback, the e-book price is often the same as the conventional-book price.

Some authors will take advantage of the costs cut by e-distribution to make money by selling e-books for very low prices. But readers aren't indifferent among books. Assuming that major publishers continue to distribute the content most people are interested in buying, they will probably hold the line on their interpretation of what a book is worth. This means that you won't save much money buying e-books if you want big publishers' content.

It's possible that some readers will skip major publishers' titles to buy $3 self-published e-books, but many readers will not be interested in exploring that territory. I think a lot of people who own e-readers are likely to do what I've done lately; buy conventional books when the price difference is less than a couple of dollars. This is because...

7. E-book formats have significant disadvantages. E-books are distributed on proprietary formats. You cannot read Apple books on a Kindle. You cannot read Kindle books on a Nook. You can read all kinds of books on iPads or PCs or phones, but you need a special app for each format. If you break your reader or decide to upgrade to a newer device, you must buy a new one from the same vendor or your old books will be incompatible with the new device. If your vendor goes out of business, your software may no longer be supported. You cannot sell or lend or give away an e-book when you finish reading it.

These are things people like to do with their books, so, to that extent, e-books are less convenient than conventional books. This inconvenience is tolerable when the e-book costs half as much as the same title in hardcover, but that may not be true if the difference is only a dollar or two.

6. Books never run out of batteries. The iPad lasts ten hours on a battery charge, and, as anyone who uses electronics knows, those batteries degrade over time, so the battery becomes less efficient. Batteries also tend to lose a charge if the device is left unplugged in standby mode. Best case scenario: an iPad battery ill last long enough to read a novel and-a-half. That kind of sucks if you want to take it on a weekend camping trip.

Dedicated e-readers do a much better job as far as power consumption. They only use power when they draw a new page on the e-ink screen, so they're off most of the time you are reading. The batteries can last weeks depending on how much you read. But there's still a chance you might pick the thing up and find it's out of juice when you want to read without being plugged in.

You never have to remember to charge a conventional book.

Tomorrow: five more reasons.

Monday, July 26, 2010

My Characters Do What I Tell Them

A lot of writers like to talk about how characters do things that surprise them, or develop in unexpected ways.

I'm of the school of thought that a story is a thing you build, not a thing you discover. When you write, you should know where you start, where you are going, and, at least roughly, how you are going to get there. This approach helps you keep the plot tight and it keeps the characters consistent and logical in their behavior.

I'm of the school of thought that a story is a thing you build, not a thing you discover. When you write, you should know where you start, where you are going, and, at least roughly, how you are going to get there. This approach helps you keep the plot tight and it keeps the characters consistent and logical in their behavior.

|

| "So, lately, I've been studying the teachings of the Buddha." |

The ever-helpful James Wood tells us that Nabokov scoffed at the idea of character autonomy; he viewed his characters as chess pieces or serfs to be moved around by the author. This is fundamentally true, but it's also a simple description of a complex process; the great trick of fiction writing is making contrived things appear organic. Characters do what they do because the author and the plot demand that they do so, but, to the reader, the characters must appear to act for their own reasons.

The characters' arcs should be carefully planned to develop with the narrative and its themes. If the character isn't who you expected him to be when you hit an important plot point, then the actions you need him to make to move the story forward might not make sense. And if you're not sure who your characters are when you start writing, it's very hard to outline a plot with that seems character-driven.

That's not to say you shouldn't pay attention to how the characters are working, or shouldn't change them over the course of the writing process. Your characters and plots and themes all develop as you revise your story, and you should constantly be asking yourself if characters' actions are consistent, logical and spring from believable motivation.

Friday, July 23, 2010

Not to piddle all over form rejection day, but...

Honest Feedback

|

| "Please feel free to query me with future projects." |

Today the Rejectionist has invited everyone to blog about form rejections to celebrate the anniversary of her hilarious blog. I've posted before about what form letters really mean, but many people still wish agents would provide real, personalized feedback. But have you ever stopped to wonder what that would actually be like?

Probably not as great as you think:

Dear Author:

I very nearly sent you our standard form rejection letter in response to your query about your novel, RAINBOWS AT SUPPERTIME, an entirely odious work you have the temerity to describe as "literary."

The form letter would have said that I am extremely busy with current clients' manuscripts, and could not responsibly take on a new book. It would have said that my editorial contacts were less than ideal for this manuscript, and your work might better be handled by another agent. It would have said that our response indicated nothing negative about your work or its prospects in the marketplace.

But that would have been a lie, and an irresponsible one. The fact is, even in a world where I had plenty of extra time, in a world where editors were far less selective in the works they were willing to publish, and where readers bought lousy books with indiscriminate abandon, I still would not represent RAINBOWS AT SUPPERTIME. You see, dear Author, I have standards.

In this business, where we must necessarily reject at least 99% of the manuscripts that come before us, it is sometimes difficult to explain exactly what it is we agents are in business to support. But it's not hard to explain what we are against. We are against RAINBOWS AT SUPPERTIME. It is offensive, both aesthetically and morally. The fact that it exists punctures my very faith in humanity.

Unpublished authors claim to like personalized responses to their submissions, and claim to desire helpful feedback. Here is some: stop submitting RAINBOWS AT SUPPERTIME. No honest or reputable agent will ever represent such a work. Offering this up to an editor would instantly destroy an agent's reputation in the publishing industry. Editors, you see, do not like to be insulted, and, frankly, neither do I. So stop wasting everybody's time.

Burn your book, Author. Destroy every copy. Erase it from your disk, format the drive, and smash your computer with a hammer.

And once that vital deed is done, in the name of all that is decent, stop writing. Stop writing at once. We in this profession hold sacred the power of the written word, and you befoul it. On some level, you have to know that RAINBOWS AT SUPPERTIME is awful. On some level, you must have been making some kind of sick joke when you submitted this. Really, Author, you should be ashamed of yourself.

If this was the form letter, this is where I would invite you to query me with any future projects. But it is my sincere hope that you never write another word, and that I never hear your name again for the rest of my life.

Best wishes,

Agent

Thursday, July 22, 2010

The coming e-pocalypse

After Amazon's triumphal chest-beating earlier this week, prognosticators of the e-pocalypse are riding high. Salon's Laura Miller imagines the future e-bookstore becoming a nightmare moonscape of noxious slush, as authors rush to e-publish their hideous and misshapen manuscripts on Kindle. Literary agent Nathan Bransford says this won't be such a bad thing. But he lives in such a place already. I agree with Miller; if e-books substantially replace conventional books, things will get a lot worse for authors and for readers.

My concern is not that technology will allow the denizens of the slushpile to disseminate their work. It's easy for authors to do that through POD and vanity presses, and it's easy for readers to ignore these books. The Internet is a vast slushpile. Anyone can publish a blog that nobody will read. I am doing it right now!

The problem, however, is that e-books could tear down the institutions that identify the gems among the slush; bookstores and publishers and agents. If e-books continue geometric growth in market share, and that growth comes at the expense of traditional book sales, bookstores will not survive. If you cut revenues in half, stores will no longer earn enough to pay staff or rent. That's true for your favorite local indie store. It's true for Barnes & Noble.

If bookstores disappear, publishers cannot continue to exist in anything like their current form. Nationwide bookstore distribution is the key service publishers offer authors that isn't available elsewhere. If the bookstores die, publishers become near obsolete; their sales mechanism isn't structured to work in a marketplace where online vendors are the only accounts. Unless they can adapt and find a way to differentiate their product from the slush on Amazon, they're not going to survive in an e-book world, just as major record labels have struggled financially as online sales killed off record stores.

In the current structure, authors who do good work differentiate from the slushpile through a very simple mechanism; they submit to agents. The agents sift out the best stuff, and submit it to publishers, who sift it again.

If that infrastructure collapses, authors who would ordinarily go through traditional channels will be kicked into a world where they have to self-publish their work and try to connect with readers entirely on their own.

But, unlike agents, media consumers aren't interested in searching for the rare gems among thousands of amateur submissions. That's not their job, and they don't have time for it. People defer to expert opinion, whether it's listening to whatever music the radio DJs are playing, or buying the books that are on the front table at Barnes and Noble.

It's likely that, in such an environment, a new tastemaker will emerge, possibly the Amazon "top reviewers." I kind of doubt their reign will be an improvement.

I suspect, instead of being paid advances in a post-bookstore world, authors will have to pay for freelance editorial, freelance marketing and publicity and freelance cover design. They'll probably have to bribe reviewers under the table, or spend a lot of time working out deals to swap positive reviews to juice their ratings. Then, in most cases, they'll still get no sales.

This situation is not an improvement for anyone except authors who would self-publish anyway. However, I still think Amazon is using the most favorable metrics to exaggerate its e-book numbers and I'm skeptical about predictions that e-books will eat the world.

|

| Social networking tools will help your book find an audience |

The problem, however, is that e-books could tear down the institutions that identify the gems among the slush; bookstores and publishers and agents. If e-books continue geometric growth in market share, and that growth comes at the expense of traditional book sales, bookstores will not survive. If you cut revenues in half, stores will no longer earn enough to pay staff or rent. That's true for your favorite local indie store. It's true for Barnes & Noble.

If bookstores disappear, publishers cannot continue to exist in anything like their current form. Nationwide bookstore distribution is the key service publishers offer authors that isn't available elsewhere. If the bookstores die, publishers become near obsolete; their sales mechanism isn't structured to work in a marketplace where online vendors are the only accounts. Unless they can adapt and find a way to differentiate their product from the slush on Amazon, they're not going to survive in an e-book world, just as major record labels have struggled financially as online sales killed off record stores.

In the current structure, authors who do good work differentiate from the slushpile through a very simple mechanism; they submit to agents. The agents sift out the best stuff, and submit it to publishers, who sift it again.

If that infrastructure collapses, authors who would ordinarily go through traditional channels will be kicked into a world where they have to self-publish their work and try to connect with readers entirely on their own.

But, unlike agents, media consumers aren't interested in searching for the rare gems among thousands of amateur submissions. That's not their job, and they don't have time for it. People defer to expert opinion, whether it's listening to whatever music the radio DJs are playing, or buying the books that are on the front table at Barnes and Noble.

It's likely that, in such an environment, a new tastemaker will emerge, possibly the Amazon "top reviewers." I kind of doubt their reign will be an improvement.

I suspect, instead of being paid advances in a post-bookstore world, authors will have to pay for freelance editorial, freelance marketing and publicity and freelance cover design. They'll probably have to bribe reviewers under the table, or spend a lot of time working out deals to swap positive reviews to juice their ratings. Then, in most cases, they'll still get no sales.

This situation is not an improvement for anyone except authors who would self-publish anyway. However, I still think Amazon is using the most favorable metrics to exaggerate its e-book numbers and I'm skeptical about predictions that e-books will eat the world.

Wednesday, July 21, 2010

Using informal language, accents and slang.

|

| "Yousa racist!" |

At the same time, if you overdo the colloquial language you create a structural barrier between your reader and your story; they can't understand what the characters are saying and they have no idea what's going on.

It's really not a sacrifice of verisimilitude to avoid excluding readers with confusing speech patterns. All dialog and narration is essentially adulterated. Although it sounds conversational in your head when you read it, good written dialog is different from the way people actually talk. And anything the reader has to stop and read twice pulls them out of the story. This is true of obscure slang terms, untranslated foreign-language phrases, run-on sentences, big SAT words, and things like references to minor characters that the reader might have to go back and look up

Adding a dialect or accent to a character's speech really doesn't change your goal much; you're still trying to capture speech that feels natural in a way that is clear on the page and doesn't present an obstacle for readers.

You don't want to add foreign language phrases that have to be translated. You don't want to use a lot of slang when the meaning isn't clear from context. You certainly don't want to represent somebody's accent by using a bunch of phonetic spelling. In the same way you don't need to describe every part of a person's face and body to give a reader a sense of the character, you don't need to lay slang and accent too thickly onto your prose to give an impression of how people speak. You can take a look at things like non-standard verb conjugations, peculiar pronoun use for non-native speakers and a few deliberately chosen foreign or slang words to really elicit a lot of voice without hanging up the reader.

Learning to utilize colloquial speech with a light touch is also useful to suggest the speaking patterns of people from backgrounds different than your own; if you apply a very thick coat of somebody else's accent or slang to a character, readers may find the portrayal offensive, especially if you get it a little bit wrong.

Of course, some writers incorporate unexplained slang and colloquial constructions into their writing with the express intention of excluding certain readers. It's an expression of identity as a point of pride, and makes no concessions to readers from outside the author's subculture. The narrative is not intended as an invitation for outsiders to peek into the author's world, so it doesn't matter if some readers don't understand what's going on; nobody invited them anyway.

Tuesday, July 20, 2010

Analyzing Amazon's Statements About Kindle Book Sales

Amazon announced its sales of e-books have outpaced hardcover book sales, at a ratio of 1.43 paid Kindle books per hardcover sold.

As is usual with information not required in corporate disclosures, this information is a little bit vague. Apple's iPad sold 3 million units in 80 days, while Kindles sold 3.7 million in the entire year. But Apple claims only 20% of the e-book market, while Amazon notes that it sells about three quarters of all James Patterson e-books, for whatever that information is worth.

Note that the ratio is calculated in a manner favorable to Amazon's boasts of robust e-book growth; the numbers are in books sold, rather than revenue. Amazon is also measuring sales for its the entire e-book catalog against hardcovers, instead of comparing sales on a title-by-title basis.

Hardcovers are prominent titles backed by current marketing pushes, so they sell a lot of copies. But they're a pretty small proportion of the total number of titles in the bookstore. Amazon stacked hardcover sales up against e-versions of the same titles, at lower prices, and e-versions of every book originally published in trade or mass market paperback format, and books published only in electronic format, and e-versions of older bestsellers that are no longer selling in hardcover. Amazon excluded free e-books from the calculation, but 80% of Amazon's e-books are $9.99 or less, while hardcovers tend to cost $15 or more. And paid Kindle books include a lot of titles priced lower than $3 and often as low as $0.99.

If Amazon were to compare overall sales (instead of only its own sales) of bestselling hardcovers to electronic versions of the same titles, the numbers would show that hardcover books are the dominant format and e-books remain a small slice of the pie.

Many analysts believe Apple is poised to crush Kindle, and that e-books will grow by piggybacking on multipurpose technologies. I'm skeptical of this myself; people buy Kindles to read books on, but they buy iPads for numerous other things, and, unlike dedicated reader devices, the iPad's ergonomics and screen are not designed specifically for book reading.

The reading experience on the iPad is severely adulterated because the screen is backlit, and therefore difficult to look at for long periods; people will not want to read on iPads for the same reasons they don't want to read books on their computer screens. The iPad, with its powerful processor and backlit LCD only lasts ten hours on a charge, so you can't take it on a camping trip or a beach weekend unless you bring a charger. The iPad screen is also hard to read in direct sunlight.. Kindle can go weeks on a charge, and traditional books are an astonishing technology that never needs to be plugged in.

Amazon made e-books attractive by paying publishers about $12.50 per e-book license, wholesale and selling them at a loss to customers for $9.99. But, as the profit margins on reader devices fall, vendor subsidies on book prices will disappear as well, and publisher pushback to Amazon's subsidized prices has brought about the agency pricing model, where publishers set prices and most bestsellers cost $12.99.

E-book sales have grown in an environment where the same content available in hardcover for $17 cost $10 on a Kindle. But when e-books are $12.99 and hardcover books are around $14, I think readers will mostly prefer paper, and paper will remain the dominant format for major-publisher releases, although low-priced e-book only releases will create a lot of opportunities for indie and niche titles.

As is usual with information not required in corporate disclosures, this information is a little bit vague. Apple's iPad sold 3 million units in 80 days, while Kindles sold 3.7 million in the entire year. But Apple claims only 20% of the e-book market, while Amazon notes that it sells about three quarters of all James Patterson e-books, for whatever that information is worth.

Note that the ratio is calculated in a manner favorable to Amazon's boasts of robust e-book growth; the numbers are in books sold, rather than revenue. Amazon is also measuring sales for its the entire e-book catalog against hardcovers, instead of comparing sales on a title-by-title basis.

Hardcovers are prominent titles backed by current marketing pushes, so they sell a lot of copies. But they're a pretty small proportion of the total number of titles in the bookstore. Amazon stacked hardcover sales up against e-versions of the same titles, at lower prices, and e-versions of every book originally published in trade or mass market paperback format, and books published only in electronic format, and e-versions of older bestsellers that are no longer selling in hardcover. Amazon excluded free e-books from the calculation, but 80% of Amazon's e-books are $9.99 or less, while hardcovers tend to cost $15 or more. And paid Kindle books include a lot of titles priced lower than $3 and often as low as $0.99.

If Amazon were to compare overall sales (instead of only its own sales) of bestselling hardcovers to electronic versions of the same titles, the numbers would show that hardcover books are the dominant format and e-books remain a small slice of the pie.

Many analysts believe Apple is poised to crush Kindle, and that e-books will grow by piggybacking on multipurpose technologies. I'm skeptical of this myself; people buy Kindles to read books on, but they buy iPads for numerous other things, and, unlike dedicated reader devices, the iPad's ergonomics and screen are not designed specifically for book reading.

The reading experience on the iPad is severely adulterated because the screen is backlit, and therefore difficult to look at for long periods; people will not want to read on iPads for the same reasons they don't want to read books on their computer screens. The iPad, with its powerful processor and backlit LCD only lasts ten hours on a charge, so you can't take it on a camping trip or a beach weekend unless you bring a charger. The iPad screen is also hard to read in direct sunlight.. Kindle can go weeks on a charge, and traditional books are an astonishing technology that never needs to be plugged in.

Amazon made e-books attractive by paying publishers about $12.50 per e-book license, wholesale and selling them at a loss to customers for $9.99. But, as the profit margins on reader devices fall, vendor subsidies on book prices will disappear as well, and publisher pushback to Amazon's subsidized prices has brought about the agency pricing model, where publishers set prices and most bestsellers cost $12.99.

E-book sales have grown in an environment where the same content available in hardcover for $17 cost $10 on a Kindle. But when e-books are $12.99 and hardcover books are around $14, I think readers will mostly prefer paper, and paper will remain the dominant format for major-publisher releases, although low-priced e-book only releases will create a lot of opportunities for indie and niche titles.

Monday, July 19, 2010

Facebook is sniffing for corpses

Facebook's crack statisticians and demographers have discovered that social networking is increasingly popular among dead people. This poses a problem; Facebook has a strong corporate anti-necromancy policy, and does not want its software to encourage you to reconnect with the deceased.

In 2007, Facebook added a feature that allows you to turn a dead person's profile into a "tribute page," but this change has to be initiated by a user, and most people don't know how to do it. So Facebook developed software to look for certain phrases in profile messages that indicate a dead user.

If you use these phrases, Facebook may dispatch a death assessment technician to your house. This person will poke you with a stick to see if you twitch. Please keep this in mind if you are prone to posting status updates like:

"Lol! My body is room-temperature."

or

"I feel fat today because the decomposition process is bloating my corpse with noxious gases."

or

"I am hungry. For BRAAAAINS."

In 2007, Facebook added a feature that allows you to turn a dead person's profile into a "tribute page," but this change has to be initiated by a user, and most people don't know how to do it. So Facebook developed software to look for certain phrases in profile messages that indicate a dead user.

If you use these phrases, Facebook may dispatch a death assessment technician to your house. This person will poke you with a stick to see if you twitch. Please keep this in mind if you are prone to posting status updates like:

"Lol! My body is room-temperature."

or

"I feel fat today because the decomposition process is bloating my corpse with noxious gases."

or

"I am hungry. For BRAAAAINS."

"I'm really into Farmville lately."

Here are several useful facts to help you get the most from your dead Facebook friends:

1. Mordant humor has been in style since before Willy Wonka cracked jokes about a little girl falling into an industrial garbage incinerator. Internet trolls know that dead people's blogs, tweets and profile pages have always been an excellent source of lulz. For example, people who die in horrific drunk driving accidents often have retrospectively ironic drunken party pictures on MySpace. Psycho killers are sometimes psycho twitters. Learn what Wonka knew: the best comedy is frequently accidental, and often has a high body-count.

"There's going to be a lot of garbage today. By which I mean dead children."

2. Facebook relies on users to help it clean up its database. It is considered good netiquette to let Facebook know about all those people you've been murdering, so it can convert their profiles to tribute pages.

The Empire is no longer friends with Alderaan.

3. When someone close to you passes, you can use Mafia Wars to send a dead fish to everyone on your shared contacts list.

"When you re-tweet this message, add a frowny-face emoticon."

4. Vampirism cannot be transmitted through Facebook, but the CDC isn't sure yet about the zombie plague.

"But if you love me, why did you change your relationship status to single?"

5. If you can't stand the humiliation of your daily life anymore, don't forget to take down any embarrassing photos before you kill yourself.

Saturday, July 17, 2010

The $75,000 book

The Wall Street Journal has a story about high-end specialty publishers selling limited-edition books with prices up to $75,000. Brett Ratner, the director of Rush Hour and X-Men 3, loves these things. And he's widely known as a consummate aesthete with discerning taste.

A book about the installation artist Christo is designed by the artist and comes with a 1965 lithograph. A book about Muhammad Ali comes with rare autographed photos. A very limited run of a book about the Indian cricket star Sachin Tendulkar is printed with ink made from Tendulkar's blood, for some reason. A book about the lunar landing comes with a piece of the moon.

"Guess what, Minions? We're in the publishing business now!"

So what other exciting limited editions can we expect? Most of these deluxe books are only for small-run, specialty titles, but my heart begins to beat faster as I imagine the tantalizing possibilities of super-fancy runs of mainstream bestsellers. For just one year's salary, you could have:

1. A limited edition of Bret Easton Ellis's Imperial Bedrooms, with a brick of commemorative cocaine. Order up some hookers and some chainsaws, and party like it's 1985!

2. A special version of Andrew Young's John Edwards tell-all, The Politician, with a rare vial of Edwards's DNA. Now you can establish the Senator's paternity in the comfort of your home!

3. Glenn Beck's The Overton Window, numbered, autographed, and soaked in a vat of the author's tears.

4. A limited edition of Stephanie Meyer's Twilight: New Moon, bound in skin from Taylor Lautner's waxed, shirtless chest. You should have read that contract more carefully, Taylor!

5. Justin Halpern's Sh*t My Dad Says, made from Halpern's father's actual shit.

6. Tucker Max's Assholes Finish First, printed with a special ink made from a pint of the author's smug sense of self-satisfaction. Fun fact: it smells kind of like Axe body spray.

Friday, July 16, 2010

Internal Consistency and Rules

Fantasy and sci-fi need to be grounded by rules. Precisely because characters in these genres have magical powers and encounter mythical creatures, their abilities need to have clearly defined constraints. We don't want to feel cheated when characters arbitrarily have new and never-before-seen powers to extricate them from plot problems.

Perhaps the most famous example of this kind of cheating is the movie Superman II, in which Superman had a magic kiss of forgetting. However, Laurell K. Hamilton's popular Anita Blake series has also been criticized for regularly giving its protagonist new superpowers to get her out of jams. This stuff isn't good; it's difficult for readers to invest in conflict if they know that the character is probably just going to solve any plot problems that arise by shooting heretofore-unmentioned laserbeams from her fingertips or blowing stuff up with her mind.

"Damn right, I have a magic kiss of forgetting. I'm friggin' Superman."

We call this deus ex machina, which is Latin for "God from the machine." The term refers to a convention of classical theater, in which plot problems were resolved by the sudden entrance of a deity into the story. However, in practice, it refers to any solution to a plot problem that emerges from outside the narrative. It is, in some ways the inverse of the well-worn rule about Chekov's gun; the rule that a gun hanging above the mantel in Act 1 must go off in Act 3. It is similarly true that, if you want the character to be packing heat in Act 3, you should establish the gun in Act 1.

Grounding something organically in plot is structurally simple; James Bond swings by the Q-Branch lab at the beginning of the movie, and Q demonstrates some new exploding cufflinks. Later on, when the villain thinks Bond is disarmed, we realized that Bond is still wearing the cufflinks. Bond will then proceed to use the cufflinks blow shit up. We understand where the cufflinks came from, so this is logical.

Compare and contrast: There are no cufflinks. When Bond is captured, he suddenly announces he has magic powers and starts blowing things up using psychokinesis or something. This is deus ex machina.

Vampire fiction has a long and dubious history of bending its own rules and loopholing its central premises. Vampires are sexy and readers love them, but their pesky problems with daylight and their inconvenient need to drink blood all the time makes it hard to write plots about how they are glamorous bad-boy romantic heroes with awesome superpowers and no drawbacks at all, whatsoever.

Twilight gets bashed a lot for its blasphemous sparkles, but beloved Buffy the Vampire Slayer struggled with similar problems, and the Buffy writers were fond of ridiculous, illogical solutions. Vampires could buy blood at the supermarket in takeout soup containers. Every building in Sunnydale was connected by convenient, easily-accessed sewers, so vampires could get around during the day. Failing that, they could run around with blankets over their heads.

"I could never love you, Spike. You smell like doody."

After the jump, more spoilery stuff about Justin Cronin's The Passage.

Thursday, July 15, 2010

Wish this were true...

Anyone seen this?

Chapter 1 of "Don't Ever Get Old":

Chapter 1 of my weird new WIP:

Chapter 1 of "Don't Ever Get Old":

I write like

David Foster Wallace

David Foster Wallace

I Write Like by Mémoires, Mac journal software. Analyze your writing!

Chapter 1 of my weird new WIP:

This software is the only critic that will ever compare me favorably to Nabokov.

Thoughts on this: from Gawker, the AV Club and The Rejectionist.

Thoughts on this: from Gawker, the AV Club and The Rejectionist.

An Inauspicious Beginning

The first chapter of "The Passage" is the story of the birth and early childhood of Amy, a character who ultimately becomes the central MacGuffin of the book. You can read first 40 pages of the book using Amazon's "look inside" feature. The opening tells us how Amy's mother, a diner waitress named Jeanette, conceived her baby during an affair with a flashy salesman who was passing through town.

The book begins with Jeanette getting pregnant and having the baby. Then her good-natured father dies. The lover returns and begins an abusive relationship with Jeanette, but she ultimately kicks him out. She struggles to make ends meet but loses her job and her home and fragile foothold on lower middle-class status. Jeanette sinks into poverty and prostitution. Six year-old Amy winds up sleeping in the bathroom at a seedy motel, while Jeanette has sex for money. Then Jeanette shoots a john who tries to rape her, ditches Amy at a convent and walks out of the story.

This takes fifteen dense pages, and I can't see the point of it. Jeanette seems entirely unnecessary. If the book began with her walking into the convent and leaving the child, with no explanation of her history or rationale, "The Passage" would be no worse off for the omission of the rest of this background information.

Maybe the Jeanette chapter has something to do with the conceit that this is a quasi-religious text; the telling of Amy's ancestry is, perhaps, intended to resemble the Biblical genealogies. But the Bible device isn't a uniform structural element throughout the story. While "found materials," diaries and letters created by some of the characters, are interspersed throughout the book, large chunks of the narrative are also written from the viewpoints of characters who die without recording their thoughts.

It's also possible that Jeanette's sad story is an indictment of the world as it exists just before everybody gets eaten by vampires. Maybe the cruelty and callousness of the society that uses and consumes and discards Jeanette is meant to be analogous to the vampire's hunger. But if Jeanette is that kind of metaphor, it's a clumsy, preachy way to start the book.

I think Jeanette is not the beginning of the story or part of the story at all. This opening chapter doesn't set any conflicts in place that continue, and it barely introduces any characters who will play a role in the story. We meet Lacey the nun who will be important later, but getting her in isn't really the focus of the chapter. We learn nothing of use about Amy. I think Cronin spends this first five-thousand words or so grinding his gears, spinning his wheels, establishing extraneous back story, and doing all the things writers should not be doing in the first chapter of a novel.

There must be a reason Cronin started where he started. He's a smart guy and a good writer; he must have looked at this chapter hundreds of times, and he must have a reason for starting here. He evidently spent years working on this book, and I'm sure a lot of thought went into where to break into the story. But I've got no idea what the rationale for this chapter might be. To me, it feels like a mistake or a miscalculation.

I guess the standard disclaimer is that Cronin gets away with this because he is uncommonly good at writing and at telling stories, but I bet some percentage of his potential readers won't get past the slow start and into the meat of the story. Not that it's hurting sales much; "The Passage" has gone viral.

The book begins with Jeanette getting pregnant and having the baby. Then her good-natured father dies. The lover returns and begins an abusive relationship with Jeanette, but she ultimately kicks him out. She struggles to make ends meet but loses her job and her home and fragile foothold on lower middle-class status. Jeanette sinks into poverty and prostitution. Six year-old Amy winds up sleeping in the bathroom at a seedy motel, while Jeanette has sex for money. Then Jeanette shoots a john who tries to rape her, ditches Amy at a convent and walks out of the story.

This takes fifteen dense pages, and I can't see the point of it. Jeanette seems entirely unnecessary. If the book began with her walking into the convent and leaving the child, with no explanation of her history or rationale, "The Passage" would be no worse off for the omission of the rest of this background information.

Maybe the Jeanette chapter has something to do with the conceit that this is a quasi-religious text; the telling of Amy's ancestry is, perhaps, intended to resemble the Biblical genealogies. But the Bible device isn't a uniform structural element throughout the story. While "found materials," diaries and letters created by some of the characters, are interspersed throughout the book, large chunks of the narrative are also written from the viewpoints of characters who die without recording their thoughts.

It's also possible that Jeanette's sad story is an indictment of the world as it exists just before everybody gets eaten by vampires. Maybe the cruelty and callousness of the society that uses and consumes and discards Jeanette is meant to be analogous to the vampire's hunger. But if Jeanette is that kind of metaphor, it's a clumsy, preachy way to start the book.

I think Jeanette is not the beginning of the story or part of the story at all. This opening chapter doesn't set any conflicts in place that continue, and it barely introduces any characters who will play a role in the story. We meet Lacey the nun who will be important later, but getting her in isn't really the focus of the chapter. We learn nothing of use about Amy. I think Cronin spends this first five-thousand words or so grinding his gears, spinning his wheels, establishing extraneous back story, and doing all the things writers should not be doing in the first chapter of a novel.

There must be a reason Cronin started where he started. He's a smart guy and a good writer; he must have looked at this chapter hundreds of times, and he must have a reason for starting here. He evidently spent years working on this book, and I'm sure a lot of thought went into where to break into the story. But I've got no idea what the rationale for this chapter might be. To me, it feels like a mistake or a miscalculation.

I guess the standard disclaimer is that Cronin gets away with this because he is uncommonly good at writing and at telling stories, but I bet some percentage of his potential readers won't get past the slow start and into the meat of the story. Not that it's hurting sales much; "The Passage" has gone viral.

Wednesday, July 14, 2010

You are the tenth rabbit.

Justin Cronin's "The Passage" is a big deal right now. It's tearing up the bestseller lists and Salon gushed over it for weeks.

It's about a vampire apocalypse, so it's got that going on. Vampires are hot. Apocalypses are hot. And Cronin is an Iowa Writers' Workshop grad with the gift for taking far-out stuff very, very seriously and pulling it off. As someone who instinctively goes for a laugh every second page, I admire and respect the ability to play things straight.

If my book had a convicted child-molester who witnessed his father's suicide and was required as a condition of his parole to take female hormones that shriveled his testicles to the size of raisins, there is no way I could play that for pathos. Especially if the character's job was to sweep glow-in-the-dark poopie out of vampire cages.

It's easy, in retrospect, to take potshots at this book. In over eight hundred pages of heart-on-its-sleeve weirdness, there are plenty of soft-spots for viral types like me to sink our needle-teeth into. "The Passage" isn't as good as Cronin seems to think it is. The subject matter never achieves the weightiness it clearly strives for. Characters who are supposed to be lovable or mysterious don't make much of an impression. Other times, extraneous background is explored unnecessarily, and the story stops for this purpose. Later on, the disposition of certain characters make this backstory feel like wasted time; there's little reason to learn about the childhood traumas or romantic foibles of a character whose narrative purpose is to get eaten by a monster.

The book contains plot holes and loose ends that clearly and obnoxiously anticipate a sequel; a book that demands this much time investment from a reader should feel more complete as a story.

But I still read the whole damn thing in less than a week, and I stayed up later than I should have to do it. And now, I want to talk about it. So if "The Passage" doesn't find a place in the literary canon, it's still compelling in its odd, sincere way, and I guess I recommend it.

Over the next couple of days I am going to pick this book apart, and talk about all the things that don't work, because exploring the stuff that is wrong with "The Passage" is potentially useful as an object lesson for writers who are interested in discussing the more abstract elements of character development and structure. But today, I want to highlight a couple of things Cronin does really well.

I'll throw a jump on the post, to hide the spoilers for people who might want to read the book. That means (in case it isn't obvious) that you have to click "read more" below in order to read the rest.

It's about a vampire apocalypse, so it's got that going on. Vampires are hot. Apocalypses are hot. And Cronin is an Iowa Writers' Workshop grad with the gift for taking far-out stuff very, very seriously and pulling it off. As someone who instinctively goes for a laugh every second page, I admire and respect the ability to play things straight.

If my book had a convicted child-molester who witnessed his father's suicide and was required as a condition of his parole to take female hormones that shriveled his testicles to the size of raisins, there is no way I could play that for pathos. Especially if the character's job was to sweep glow-in-the-dark poopie out of vampire cages.

It's easy, in retrospect, to take potshots at this book. In over eight hundred pages of heart-on-its-sleeve weirdness, there are plenty of soft-spots for viral types like me to sink our needle-teeth into. "The Passage" isn't as good as Cronin seems to think it is. The subject matter never achieves the weightiness it clearly strives for. Characters who are supposed to be lovable or mysterious don't make much of an impression. Other times, extraneous background is explored unnecessarily, and the story stops for this purpose. Later on, the disposition of certain characters make this backstory feel like wasted time; there's little reason to learn about the childhood traumas or romantic foibles of a character whose narrative purpose is to get eaten by a monster.

The book contains plot holes and loose ends that clearly and obnoxiously anticipate a sequel; a book that demands this much time investment from a reader should feel more complete as a story.

But I still read the whole damn thing in less than a week, and I stayed up later than I should have to do it. And now, I want to talk about it. So if "The Passage" doesn't find a place in the literary canon, it's still compelling in its odd, sincere way, and I guess I recommend it.

Over the next couple of days I am going to pick this book apart, and talk about all the things that don't work, because exploring the stuff that is wrong with "The Passage" is potentially useful as an object lesson for writers who are interested in discussing the more abstract elements of character development and structure. But today, I want to highlight a couple of things Cronin does really well.

I'll throw a jump on the post, to hide the spoilers for people who might want to read the book. That means (in case it isn't obvious) that you have to click "read more" below in order to read the rest.

Tuesday, July 13, 2010

Getting the character in

In "How Fiction Works," which I continue to recommend, James Wood talks about how many novels begin with what he calls "descriptions of photographs," scenes where characters are introduced by describing their appearance or their manner of dress.

I've posted before about the common misconception that a novel needs to start with action of the car-chase/swordfight variety. But it bears repeating, because a lot of authors struggle with first pages, and first pages are very important.

Your goal as an author is to quickly introduce a character and a problem.

Dropping into the story in the middle of a swordfight usually isn't the best way to do this. When you have action without context, there's nothing at stake and the reader won't engage with it. Your introduction to the character gets buried in the mechanical details of the fight or the chase, and the set piece ends up being counterproductive. The fight is all surface detail, another way of describing a photograph.

A good first page could be a character sitting in an exam room at a doctor's office, waiting for a test result.

A good first page could be the protagonist telling his wife a lie.

Your goal is to show the reader something about the character and to engage the reader in what is going to happen next.

What you don't want to be doing on the first page is describing a house or a town, or talking about what a character looks like. A lot of great authors have begun books by establishing the setting and then zooming in toward the character, but it's out of style in a contemporary novel, and these openings are often obstacles the reader has to get past to get into the story.

There is a very good, very valid rule that something needs to start happening immediately in a book. The thing that happens should be beginning of the story.

The rule is to grab the reader and not let go, but action sequences are not what grabs readers. When you have action without context, there's nothing at stake and the reader won't engage with it. Your introduction to the character gets buried in the mechanical details of the fight or the chase, and the set piece ends up being counterproductive.

I've posted before about the common misconception that a novel needs to start with action of the car-chase/swordfight variety. But it bears repeating, because a lot of authors struggle with first pages, and first pages are very important.

Your goal as an author is to quickly introduce a character and a problem.

Dropping into the story in the middle of a swordfight usually isn't the best way to do this. When you have action without context, there's nothing at stake and the reader won't engage with it. Your introduction to the character gets buried in the mechanical details of the fight or the chase, and the set piece ends up being counterproductive. The fight is all surface detail, another way of describing a photograph.

A good first page could be a character sitting in an exam room at a doctor's office, waiting for a test result.

A good first page could be the protagonist telling his wife a lie.

Your goal is to show the reader something about the character and to engage the reader in what is going to happen next.

What you don't want to be doing on the first page is describing a house or a town, or talking about what a character looks like. A lot of great authors have begun books by establishing the setting and then zooming in toward the character, but it's out of style in a contemporary novel, and these openings are often obstacles the reader has to get past to get into the story.

There is a very good, very valid rule that something needs to start happening immediately in a book. The thing that happens should be beginning of the story.

The rule is to grab the reader and not let go, but action sequences are not what grabs readers. When you have action without context, there's nothing at stake and the reader won't engage with it. Your introduction to the character gets buried in the mechanical details of the fight or the chase, and the set piece ends up being counterproductive.

Thursday, July 8, 2010

Story is different from life

Nathan Bransford compares novels that sacrifice story in the interest of verisimilitude to undercooked meals.

I don't know if I entirely agree with the undercooking metaphor, but his underlying point is close to absolute truth for just about all writers.

Life is a bunch of stuff that happens; most of it is confusing and some of it is arbitrary. Narrative is a series of events that occur through a perceivable chain of cause and effect. Important things must be introduced, and extraneous things must be omitted. Narrative is, to some extent, an artificial construct, whether it's employed to recount true events or fictional ones. But it's ironclad and non-negotiable.

If you are morally or aesthetically opposed to the idea of a story, I sympathize with you. I kind of feel that way myself. But, if you want to write fiction for publication, I think you have to reconcile yourself to the conventions of Western storytelling.

If your theme or subject matter is the arbitrary and unexplainable, and your novel is therefore a frontal attack on the central conceit of the story, you've got your work cut out for you. Literary agents who enjoy eating food and acquiring editors who enjoy having jobs may admire your devotion to your ideals and your experimental aspirations. But they'll probably admire you from a safe distance.

It helps, I guess, if you are an extraordinary talent; the kind of person who can describe grass in a way that makes readers break down weeping. And even then, the best-case scenario for the amazing talents who are steadfast in their refusal to bend to commercial norms is that they end up being one of the National Book Award nominees that only 1,500 people read.

I don't know if I entirely agree with the undercooking metaphor, but his underlying point is close to absolute truth for just about all writers.

Life is a bunch of stuff that happens; most of it is confusing and some of it is arbitrary. Narrative is a series of events that occur through a perceivable chain of cause and effect. Important things must be introduced, and extraneous things must be omitted. Narrative is, to some extent, an artificial construct, whether it's employed to recount true events or fictional ones. But it's ironclad and non-negotiable.

If you are morally or aesthetically opposed to the idea of a story, I sympathize with you. I kind of feel that way myself. But, if you want to write fiction for publication, I think you have to reconcile yourself to the conventions of Western storytelling.

If your theme or subject matter is the arbitrary and unexplainable, and your novel is therefore a frontal attack on the central conceit of the story, you've got your work cut out for you. Literary agents who enjoy eating food and acquiring editors who enjoy having jobs may admire your devotion to your ideals and your experimental aspirations. But they'll probably admire you from a safe distance.

It helps, I guess, if you are an extraordinary talent; the kind of person who can describe grass in a way that makes readers break down weeping. And even then, the best-case scenario for the amazing talents who are steadfast in their refusal to bend to commercial norms is that they end up being one of the National Book Award nominees that only 1,500 people read.

Tuesday, July 6, 2010

Want to write? Start reading.

You have to read. A lot. And you have to read good books.

You should read a lot before you ever start writing. Reading is how you learn what a good sentence feels like. Reading helps you develop your command of the finer points of grammar and syntax. Reading improves your vocabulary.

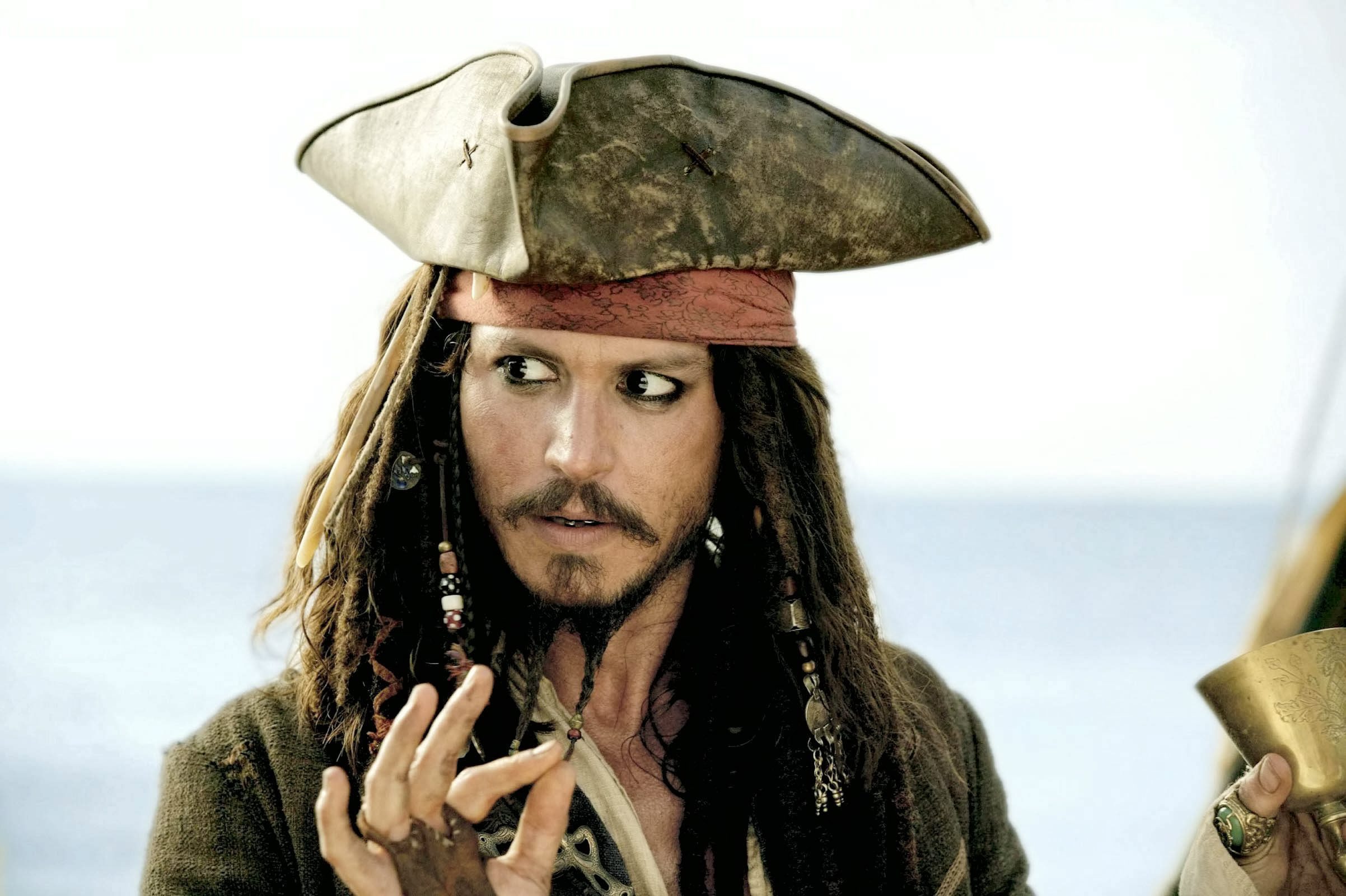

Reading is also the best way to learn about plot and structure. If you don't know where to begin and to end, you need to read, to learn the shape of a story. Movies can also help you with learning about narrative structure, since they compress the whole enterprise into about two hours. Watch, in particular, how they open and how they introduce characters. The wedding scene in "The Godfather" and the montage introducing the gang in "Ocean's Eleven" are remarkably cool and efficient examples of how to introduce a large cast quickly, without resorting to excessive exposition. If you want to learn how to establish characters, those movies are a good place to start.

You can also learn a lot from watching TV, if you watch the good shows and pay attention to plotting and structure. Television's narrative objective is to sustain narrative tension and viewer interest while moving the plot slowly. In a novel, things happen faster, and maintaining a status quo is less of an underlying objective, but tension remains important. You can learn some good story tricks from serialized dramas like "Lost" and "Mad Men."

Reading will also help make things like dialog and description second nature. Dialog that works on the page is a little different from the way people actually talk, but it feels natural. And many things people say, the pleasantries and small talk, are excluded on the page. If your dialog is clunky or awkward you need to read more, to learn how to write it. Description should be evocative without getting purple or taking up too much space. The best way to learn how to do these things is to see them done well.

If you aren't well-read, you are probably working with an incomplete toolbox.

You should read a lot before you ever start writing. Reading is how you learn what a good sentence feels like. Reading helps you develop your command of the finer points of grammar and syntax. Reading improves your vocabulary.

Reading is also the best way to learn about plot and structure. If you don't know where to begin and to end, you need to read, to learn the shape of a story. Movies can also help you with learning about narrative structure, since they compress the whole enterprise into about two hours. Watch, in particular, how they open and how they introduce characters. The wedding scene in "The Godfather" and the montage introducing the gang in "Ocean's Eleven" are remarkably cool and efficient examples of how to introduce a large cast quickly, without resorting to excessive exposition. If you want to learn how to establish characters, those movies are a good place to start.

"We have three minutes to introduce nine characters. Are you in, or are you out?"

You can also learn a lot from watching TV, if you watch the good shows and pay attention to plotting and structure. Television's narrative objective is to sustain narrative tension and viewer interest while moving the plot slowly. In a novel, things happen faster, and maintaining a status quo is less of an underlying objective, but tension remains important. You can learn some good story tricks from serialized dramas like "Lost" and "Mad Men."

Reading will also help make things like dialog and description second nature. Dialog that works on the page is a little different from the way people actually talk, but it feels natural. And many things people say, the pleasantries and small talk, are excluded on the page. If your dialog is clunky or awkward you need to read more, to learn how to write it. Description should be evocative without getting purple or taking up too much space. The best way to learn how to do these things is to see them done well.

If you aren't well-read, you are probably working with an incomplete toolbox.

Monday, July 5, 2010

Saturday, July 3, 2010

Easy solutions to difficult problems

Shalom Auslander has a problem. When he sits down to write, a bunch of disembodied voices sit down with him, flooding his head, filling him with self-doubt. Have you ever tried to make progress on a story while Hitler is whispering in your ear? It ain't no picnic.

Fortunately, I have the answer. Thank me in the acknowledgements, Bro.

Fortunately, I have the answer. Thank me in the acknowledgements, Bro.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)